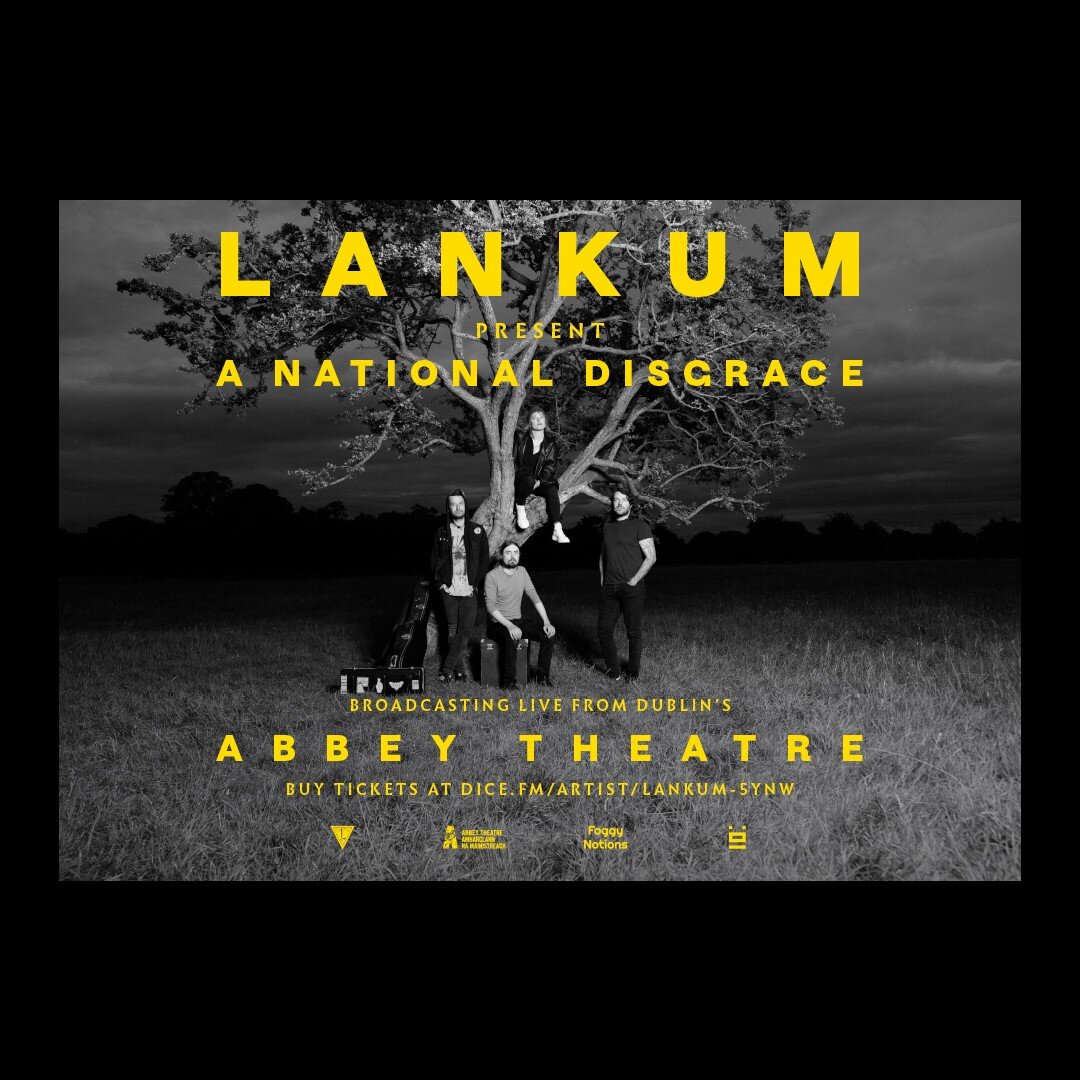

LANKUM present A NATIONAL DISGRACE: A REVIEW

By Jack Garton

I spent last night watching and then re-watching a strange, exhilarating new genre of performance art. Although the thought of yet another live stream vying to fill the gig-shaped hole in my heart makes me want to throw my computer in a garbage compactor, I was intrigued by Lankum’s cryptic description of their upcoming show called A NATIONAL DISGRACE. A hallucinatory, immersive blend of music, comedy and performance art, referencing a night at Dublin’s Abbey theatre almost a hundred years ago, when a stern W.B. Yeats scolded the rioting audience, “You have disgraced yourselves again!”; only this time, amid a global pandemic, the theatre would be empty. I’ve been a fan of the Irish apocalyptic trad band Lankum for about a year now, catching up on their career ravenously, loving their combination of sean-nós, killer trad playing, protest songs and shuddering analog drones. But what I like most about them is their ability to lash history to the present so thoroughly and compellingly, that they are creating a new future. Capitalism creates echo chambers of market-friendly product out of music cultures deemed ‘ethnic’ in some way, defanging the underdog democratic power of the folk music process. Like many a North American, I’m too familiar with the increasingly smooth, pre-packaged version of Irish traditional music, compared to which Lankum feels rough and jarring, maybe even revolutionary. But at the root of each of their innovations is an anchor in the tradition.

WHAT DID WE LOSE?

During last night’s show, one of the many interstitial archival interview clips references this sense that a living musical tradition can get lost in translation. When we recently stopped being able to experience music live, what did we lose? As the band drones ominously, an Irish voice from the past intones:

“The fiddlers who play this tune on the wireless didn’t play it right…they made a very bad job of the tune…if all other music is treated the same as the piece that I composed myself, I think that if Schubert and Beethoven and all the other composers came back and heard their music changed so much, I wonder what would they think?”

This and other well-chosen quotes, broadcasted over textured musical interludes, are so illuminating to the songs they frame, so revelatory to the band’s relationship with the tradition, I would venture to say that this entire performance as a text on Irish musical and cultural history is a momentous achievement in itself. But that’s not even the best thing about the show.

On one level, it was simply a great musical performance. Using a collection of traditional and contemporary instruments, all with gorgeous tones and well live-mixed (more on the production value later), the band played two sets of songs, mostly from their recent album The Livelong Day. The arrangements were signature Lankum: crunchy, almost dissonant chords, long forms suited to building tension, with masterfully placed moments of cathartic release. It’s moody as f***, but a sense of play and spontaneity still manages to prevail, whether its Radie Peat playing the harmonium with her foot or putting a few new beautiful vocal inflections on familiar melodies from the album, or Darragh Lynch sawing at his guitar with a bow, or just the fact that any time Ian Lynch closes his eyes and opens his mouth to sing, his complete absorption and vulnerability would thaw to life a heart of permafrost. Cormac Dermody sits calmly amid all of it, supernaturally still, his unexpected octave jumps combine with the reed instruments to create a breathless, panting feeling. He’s clearly a virtuoso fiddler, but as with the other players, he rarely plays ‘tunes’ as we’d expect, instead each submits themselves to the arrangements, creating something much larger and more awe-inspiring than the sum of its parts.

It’s not just the music that inspires awe, but the perfectly-pitched lighting design by Kevin McFadden, the pristine live sound by John ‘Spud’ Murphy, and the smooth, evocative camera work orchestrated by James Clarke. While so many live streaming concerts succumb to technical difficulties that force us out of the moment and drive home their inferiority to live gigs, this one was as smooth and artistic as a feature film, while never losing the live feeling, at times creating an uncanny sense of life seeming more artful than life: the very feeling one gets at an incredible live show. The production team deserves full credit for somehow creating and maintaining both the spectacle and the intimacy online, in a way I’ve never yet felt.

The intimacy is created in a way I’d never have expected to work so well. It’s done by including musical and comedic cameos before, between, and after the sets, revealed in the form of a hand-held point-of-view camera-as-audience-member exploring the historic Abbey Theatre, happening upon behind-the-scenes action. We get to feel intimate with the space in ways that feel illicit, absorbing and disarming. One of the things we’ve lost about live performance that makes it so powerful is the ritualistic sense of place. An important aspect of the ritual is the journey away from our normal environment to witness the magical space of the show, where possibilities are different from those in our bedroom.

WILD ROVING

Thus, A NATIONAL DISGRACE begins in a taxi cab on a Dublin street, on our way to the gig. We are dropped at the door (by none other than the Lynch brothers’ actual cab driver dad) and led into the theatre somewhat cryptically, hearing the familiar sound of “…please turn off your cellular device…the show is about to begin”. A gorgeous scrim rises, and the band plays a fantastic first set. The second song, The Young People, gives me chills and is worth the price of admission alone. At intermission, things get weird when the sound of maniacal laughter leads us up the empty aisle into the lobby where we are supposedly looking for the toilet. We wander the hallways of the Abbey stumbling upon beautifully abstract and fun performances by Hugh Cooney, Acid Granny, The Mary Wallopers and Natalia Beylis, each of which could be talked about at length with themes pitched perfectly to enrich those of the main musical performance. Plus, what live gig is complete without accidentally running into some weirdos in rooms you’re not sure you’re allowed to be in? It’s the wide and bizarre leaps in tone that triumph here, from poetic to corny to terrifying, by the time intermission is over it’s hard to believe I could feel so many things in ten minutes.

The show reconvenes with a “last call” (the disembodied voice of Andy the Doorbum) and a recording of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” slowly and eerily winding down into the first tense notes of Lankum’s arrangement of The Wild Rover. This particular song is a good example of the band taking a piece of music so familiar as to seem stereotypical, but through research and diligent song collection practice, reaching back into the past and pulling it into the present in a whole new light. Their commitment to learning and uncovering the roots of their tradition proposes a universally compelling way to be a musician in this generation. The soul feels refreshed in their presence, as when admiring the rings of a tree in hand-milled lumber, or when leaving the city, finding somewhere truly dark and looking up into a sky endless with stars.

The second set includes many pitch-black ballads, slowly winding up tension with sallow masterpieces like Hunting the Wren and Katie Cruel. While the latter needs to be mentioned for Katie Kim’s haunting high vocal (present on the album but so much more visceral live) the former contains what could be the show’s most singularly brilliant line:

“There are birds of the air,

And beasts of the field

By spite and by fury,

are people revealed”

In this song the image of the wren is used to tell the story of the Curragh Wrens, women who were outcast and subject to brutal violence, taking their chances living outdoors on the plains of Kildare. Another kind of revelation comes when at last Cormac Dermody plays the final tune, Bear Creek, and the supporting instruments after a long, oblique buildup suddenly stop, then unleash full-throated major chords beneath his fiddle; the cathartic effect is as wide and spacious as seeing the ocean for the first time. We’ve arrived somewhere special, and our senses, heightened by the relentless pacing of the set, can appreciate the simple melody and chords for the pure magic that they are.

BACKSTAGE

After the scrim falls for the final time, we don’t exit into the lobby, but instead descend deeper into the bowels of the Abbey, where strange moaning leads us to venture into a props room that resembles a hoarder’s den. Here, Tony Cantwell delivers a hilarious and unsettling monologue emblematic of our global predicament: stuck alone and going mad in rooms, surrounded by nothing but our possessions, yearning for some human contact and clinging to superstition. It’s funny and sad. It would make a great work of fiction - it’s all truth. Not willing to stay there forever though, we back away from that room and open a door further down the hall to a blistering, furious performance by Kneecap. Strobe lights blare, and the sound hits like a bomb. The three young hardcore rappers are literally bouncing off walls reminiscent of an asylum. The youngest performers in the show, their raw energy bubbling underground is strangely beautiful. After being chased out of the room, one more song calls us onward; as we ascend a back staircase, following the sound, we can see that it’s the band, lounging in the loading bay with beers in hand, in a sing-along led by the Abbey doorman that ends in raucous laughter. One final intimacy.

THE FUTURE WE NEED

Lankum’s early work under the name Lynched included passionate anti-capitalist rants, raw-voiced and smart. These are now mostly replaced by thoroughly researched and carefully chosen traditionals, and originals that verge on lyrical minimalism, delivered with focused control. The approach has deepened. By centring the stories of the marginalized, old and new, and making them current conversation, by including the voices of elders, and by lifting up their local artistic community along with them, their current work is a direct refutation of music as merely a commodity. Instead of railing against a future we don’t want, they are creating the future we need. Despite, or in fact because of, the fact that their work is deeply locally-rooted, it’s relevant to the way young folk musicians around the world can engage with their own history and musical tradition.

It’s now the next day, and the stream has vanished from the internet. As powerful and monumental as it was, it’s now gone. This is the show’s crowning glory. As death gives meaning to life, a sense of time is what gives live performance its meaning, allows it to impact the trajectory of our lives the way on-demand culture never will and only wishes it could. I’ve heard it said that we are living in a ‘golden age’ of entertainment, with Netflix, Amazon and many others claiming to offer us the best stories at a better convenience than has ever been dreamed. Well, last night A NATIONAL DISGRACE, with it’s stunning depth and integrity, gracefully blew that model out of the water by being so much better.

Learn more about the band here

-Jack Garton is a songwriter, gravedigger and father. He lives on Galiano island in the Salish Sea.